Deadline: July 1, 2024 Who is that great instructor that inspired or encouraged you to do oral history? The Oral History Association is accepting nominations for the Cliff Kuhn Postsecondary Teaching Award. If you have a teacher, past or present, who has integrated oral history into their teaching, now is the time to shine a […]

When Online Content Disappears

We research words and content for our transcripts. Words that we aren’t sure of, we look up to verify spelling and validity. We got this article from https://www.pewresearch.org/?p=167501. If you’re intrigued, sign up for the Pew Research Newsletter.

Our object is to capture the spoken word, and people make vague references, sometimes to places that no longer exist. Some of the oral histories we transcribe reference events that happened a long time ago—World War II, for example. So we spend a lot of time researching. AI doesn’t verify terms, but we do—we try to verify everything we can.

How they did the study:

How we did this

Pew Research Center conducted the analysis to examine how often online content that once existed becomes inaccessible. One part of the study looks at a representative sample of webpages that existed over the past decade to see how many are still accessible today. For this analysis, we collected a sample of pages from the Common Crawl web repository for each year from 2013 to 2023. We then tried to access those pages to see how many still exist.

A second part of the study looks at the links on existing webpages to see how many of those links are still functional. We did this by collecting a large sample of pages from government websites, news websites and the online encyclopedia Wikipedia.

We identified relevant news domains using data from the audience metrics company comScore and relevant government domains (at multiple levels of government) using data from get.gov, the official administrator for the .gov domain. We collected the news and government pages via Common Crawl and the Wikipedia pages from an archive maintained by the Wikimedia Foundation. For each collection, we identified the links on those pages and followed them to their destination to see what share of those links point to sites that are no longer accessible.

A third part of the study looks at how often individual posts on social media sites are deleted or otherwise removed from public view. We did this by collecting a large sample of public tweets on the social media platform X (then known as Twitter) in real time using the Twitter Streaming API. We then tracked the status of those tweets for a period of three months using the Twitter Search API to monitor how many were still publicly available. Refer to the report methodology for more details.

The internet is an unimaginably vast repository of modern life, with hundreds of billions of indexed webpages. But even as users across the world rely on the web to access books, images, news articles and other resources, this content sometimes disappears from view.

A new Pew Research Center analysis shows just how fleeting online content actually is:

A quarter of all webpages that existed at one point between 2013 and 2023 are no longer accessible, as of October 2023. In most cases, this is because an individual page was deleted or removed on an otherwise functional website.

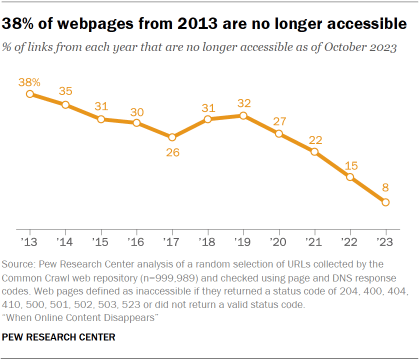

For older content, this trend is even starker. Some 38% of webpages that existed in 2013 are not available today, compared with 8% of pages that existed in 2023.

This “digital decay” occurs in many different online spaces. We examined the links that appear on government and news websites, as well as in the “References” section of Wikipedia pages as of spring 2023. This analysis found that:

23% of news webpages contain at least one broken link, as do 21% of webpages from government sites. News sites with a high level of site traffic and those with less are about equally likely to contain broken links. Local-level government webpages (those belonging to city governments) are especially likely to have broken links.

54% of Wikipedia pages contain at least one link in their “References” section that points to a page that no longer exists.

To see how digital decay plays out on social media, we also collected a real-time sample of tweets during spring 2023 on the social media platform X (then known as Twitter) and followed them for three months. We found that:

Nearly one-in-five tweets are no longer publicly visible on the site just months after being posted. In 60% of these cases, the account that originally posted the tweet was made private, suspended or deleted entirely. In the other 40%, the account holder deleted the individual tweet, but the account itself still existed.

Certain types of tweets tend to go away more often than others. More than 40% of tweets written in Turkish or Arabic are no longer visible on the site within three months of being posted. And tweets from accounts with the default profile settings are especially likely to disappear from public view.

How this report defines inaccessible links and webpages

There are many ways of defining whether something on the internet that used to exist is now inaccessible to people trying to reach it today. For instance, “inaccessible” could mean that:

The page no longer exists on its host server, or the host server itself no longer exists. Someone visiting this type of page would typically receive a variation on the “404 Not Found” server error instead of the content they were looking for.

The page address exists but its content has been changed – sometimes dramatically – from what it was originally.

The page exists but certain users – such as those with blindness or other visual impairments – might find it difficult or impossible to read.

For this report, we focused on the first of these: pages that no longer exist. The other definitions of accessibility are beyond the scope of this research.

Our approach is a straightforward way of measuring whether something online is accessible or not. But even so, there is some ambiguity.

First, there are dozens of status codes indicating a problem that a user might encounter when they try to access a page. Not all of them definitively indicate whether the page is permanently defunct or just temporarily unavailable. Second, for security reasons, many sites actively try to prevent the sort of automated data collection that we used to test our full list of links.

For these reasons, we used the most conservative estimate possible for deciding whether a site was actually accessible or not. We counted pages as inaccessible only if they returned one of nine error codes that definitively indicate that the page and/or its host server no longer exist or have become nonfunctional – regardless of how they are being accessed, and by whom. The full list of error codes that we included in our definition are in the methodology.

Here are some of the findings from our analysis of digital decay in various online spaces.

Webpages from the last decade

To conduct this part of our analysis, we collected a random sample of just under 1 million webpages from the archives of Common Crawl, an internet archive service that periodically collects snapshots of the internet as it exists at different points in time. We sampled pages collected by Common Crawl each year from 2013 through 2023 (approximately 90,000 pages per year) and checked to see if those pages still exist today.

We found that 25% of all the pages we collected from 2013 through 2023 were no longer accessible as of October 2023. This figure is the sum of two different types of broken pages: 16% of pages are individually inaccessible but come from an otherwise functional root-level domain; the other 9% are inaccessible because their entire root domain is no longer functional.

Not surprisingly, the older snapshots in our collection had the largest share of inaccessible links. Of the pages collected from the 2013 snapshot, 38% were no longer accessible in 2023. But even for pages collected in the 2021 snapshot, about one-in-five were no longer accessible just two years later.

Links on government websites

We sampled around 500,000 pages from government websites using the Common Crawl March/April 2023 snapshot of the internet, including a mix of different levels of government (federal, state, local and others). We found every link on each page and followed a random selection of those links to their destination to see if the pages they refer to still exist.

The vast majority go to secure HTTP pages (and have a URL starting with “https://”).

6% go to a static file, like a PDF document.

16% now redirect to a different URL than the one they originally pointed to.

When we followed these links, we found that 6% point to pages that are no longer accessible. Similar shares of internal and external links are no longer functional.

Links on news websites

For this analysis, we sampled 500,000 pages from 2,063 websites classified as “News/Information” by the audience metrics firm comScore. The pages were collected from the Common Crawl March/April 2023 snapshot of the internet.

Reference links on Wikipedia

For this analysis, we collected a random sample of 50,000 English-language Wikipedia pages and examined the links in their “References” section. The vast majority of these pages (82%) contain at least one reference link – that is, one that directs the reader to a webpage other than Wikipedia itself.

Posts on Twitter

For this analysis, we collected nearly 5 million tweets posted from March 8 to April 27, 2023, on the social media platform X, which at the time was known as Twitter. We did this using Twitter’s Streaming API, collecting 3,000 public tweets every 30 minutes in real time. This provided us with a representative sample of all tweets posted on the platform during that period. We monitored those tweets until June 15, 2023, and checked each day to see if they were still available on the site or not.

Which tweets tend to disappear?

Tweets were especially likely to be deleted or removed over the course of our collection period if they were:

Written in certain languages. Nearly half of all the Turkish-language tweets we collected – and a slightly smaller share of those written in Arabic – were no longer available at the end of the tracking period.

Posted by accounts using the site’s default profile settings. More than half of tweets from accounts using the default profile image were no longer available at the end of the tracking period, as were more than a third from accounts with a default bio field. Tweets from these accounts tend to disappear because the entire account has been deleted or made private, as opposed to the individual tweet being deleted.

Posted by unverified accounts.

We also found that removed or deleted tweets tended to come from newer accounts with relatively few followers and modest activityon the site. On average, tweets that were no longer visible on the site were posted by accounts around eight months younger than those whose tweets stayed on the site.

1% of tweets are removed within one hour

3% within a day

10% within a week

15% within a month

Put another way: Half of tweets that are eventually removed from the platform are unavailable within the first six days of being posted. And 90% of these tweets are unavailable within 46 days.

When Online Content Disappears

We research words and content for our transcripts. Words that we aren’t sure of, we look up to verify spelling and validity. We got this article from https://www.pewresearch.org/?p=167501. If you’re intrigued, sign up for the Pew Research Newsletter.

Our object is to capture the spoken word, and people make vague references, sometimes to places that no longer exist. Some of the oral histories we transcribe reference events that happened a long time ago—World War II, for example. So we spend a lot of time researching. AI doesn’t verify terms, but we do—we try to verify everything we can.

How they did the study:

How we did this

Pew Research Center conducted the analysis to examine how often online content that once existed becomes inaccessible. One part of the study looks at a representative sample of webpages that existed over the past decade to see how many are still accessible today. For this analysis, we collected a sample of pages from the Common Crawl web repository for each year from 2013 to 2023. We then tried to access those pages to see how many still exist.

A second part of the study looks at the links on existing webpages to see how many of those links are still functional. We did this by collecting a large sample of pages from government websites, news websites and the online encyclopedia Wikipedia.

We identified relevant news domains using data from the audience metrics company comScore and relevant government domains (at multiple levels of government) using data from get.gov, the official administrator for the .gov domain. We collected the news and government pages via Common Crawl and the Wikipedia pages from an archive maintained by the Wikimedia Foundation. For each collection, we identified the links on those pages and followed them to their destination to see what share of those links point to sites that are no longer accessible.

A third part of the study looks at how often individual posts on social media sites are deleted or otherwise removed from public view. We did this by collecting a large sample of public tweets on the social media platform X (then known as Twitter) in real time using the Twitter Streaming API. We then tracked the status of those tweets for a period of three months using the Twitter Search API to monitor how many were still publicly available. Refer to the report methodology for more details.

The internet is an unimaginably vast repository of modern life, with hundreds of billions of indexed webpages. But even as users across the world rely on the web to access books, images, news articles and other resources, this content sometimes disappears from view.

A new Pew Research Center analysis shows just how fleeting online content actually is:

A quarter of all webpages that existed at one point between 2013 and 2023 are no longer accessible, as of October 2023. In most cases, this is because an individual page was deleted or removed on an otherwise functional website.

For older content, this trend is even starker. Some 38% of webpages that existed in 2013 are not available today, compared with 8% of pages that existed in 2023.

This “digital decay” occurs in many different online spaces. We examined the links that appear on government and news websites, as well as in the “References” section of Wikipedia pages as of spring 2023. This analysis found that:

23% of news webpages contain at least one broken link, as do 21% of webpages from government sites. News sites with a high level of site traffic and those with less are about equally likely to contain broken links. Local-level government webpages (those belonging to city governments) are especially likely to have broken links.

54% of Wikipedia pages contain at least one link in their “References” section that points to a page that no longer exists.

To see how digital decay plays out on social media, we also collected a real-time sample of tweets during spring 2023 on the social media platform X (then known as Twitter) and followed them for three months. We found that:

Nearly one-in-five tweets are no longer publicly visible on the site just months after being posted. In 60% of these cases, the account that originally posted the tweet was made private, suspended or deleted entirely. In the other 40%, the account holder deleted the individual tweet, but the account itself still existed.

Certain types of tweets tend to go away more often than others. More than 40% of tweets written in Turkish or Arabic are no longer visible on the site within three months of being posted. And tweets from accounts with the default profile settings are especially likely to disappear from public view.

How this report defines inaccessible links and webpages

There are many ways of defining whether something on the internet that used to exist is now inaccessible to people trying to reach it today. For instance, “inaccessible” could mean that:

The page no longer exists on its host server, or the host server itself no longer exists. Someone visiting this type of page would typically receive a variation on the “404 Not Found” server error instead of the content they were looking for.

The page address exists but its content has been changed – sometimes dramatically – from what it was originally.

The page exists but certain users – such as those with blindness or other visual impairments – might find it difficult or impossible to read.

For this report, we focused on the first of these: pages that no longer exist. The other definitions of accessibility are beyond the scope of this research.

Our approach is a straightforward way of measuring whether something online is accessible or not. But even so, there is some ambiguity.

First, there are dozens of status codes indicating a problem that a user might encounter when they try to access a page. Not all of them definitively indicate whether the page is permanently defunct or just temporarily unavailable. Second, for security reasons, many sites actively try to prevent the sort of automated data collection that we used to test our full list of links.

For these reasons, we used the most conservative estimate possible for deciding whether a site was actually accessible or not. We counted pages as inaccessible only if they returned one of nine error codes that definitively indicate that the page and/or its host server no longer exist or have become nonfunctional – regardless of how they are being accessed, and by whom. The full list of error codes that we included in our definition are in the methodology.

Here are some of the findings from our analysis of digital decay in various online spaces.

Webpages from the last decade

To conduct this part of our analysis, we collected a random sample of just under 1 million webpages from the archives of Common Crawl, an internet archive service that periodically collects snapshots of the internet as it exists at different points in time. We sampled pages collected by Common Crawl each year from 2013 through 2023 (approximately 90,000 pages per year) and checked to see if those pages still exist today.

We found that 25% of all the pages we collected from 2013 through 2023 were no longer accessible as of October 2023. This figure is the sum of two different types of broken pages: 16% of pages are individually inaccessible but come from an otherwise functional root-level domain; the other 9% are inaccessible because their entire root domain is no longer functional.

Not surprisingly, the older snapshots in our collection had the largest share of inaccessible links. Of the pages collected from the 2013 snapshot, 38% were no longer accessible in 2023. But even for pages collected in the 2021 snapshot, about one-in-five were no longer accessible just two years later.

Links on government websites

We sampled around 500,000 pages from government websites using the Common Crawl March/April 2023 snapshot of the internet, including a mix of different levels of government (federal, state, local and others). We found every link on each page and followed a random selection of those links to their destination to see if the pages they refer to still exist.

The vast majority go to secure HTTP pages (and have a URL starting with “https://”).

6% go to a static file, like a PDF document.

16% now redirect to a different URL than the one they originally pointed to.

When we followed these links, we found that 6% point to pages that are no longer accessible. Similar shares of internal and external links are no longer functional.

Links on news websites

For this analysis, we sampled 500,000 pages from 2,063 websites classified as “News/Information” by the audience metrics firm comScore. The pages were collected from the Common Crawl March/April 2023 snapshot of the internet.

Reference links on Wikipedia

For this analysis, we collected a random sample of 50,000 English-language Wikipedia pages and examined the links in their “References” section. The vast majority of these pages (82%) contain at least one reference link – that is, one that directs the reader to a webpage other than Wikipedia itself.

Posts on Twitter

For this analysis, we collected nearly 5 million tweets posted from March 8 to April 27, 2023, on the social media platform X, which at the time was known as Twitter. We did this using Twitter’s Streaming API, collecting 3,000 public tweets every 30 minutes in real time. This provided us with a representative sample of all tweets posted on the platform during that period. We monitored those tweets until June 15, 2023, and checked each day to see if they were still available on the site or not.

Which tweets tend to disappear?

Tweets were especially likely to be deleted or removed over the course of our collection period if they were:

Written in certain languages. Nearly half of all the Turkish-language tweets we collected – and a slightly smaller share of those written in Arabic – were no longer available at the end of the tracking period.

Posted by accounts using the site’s default profile settings. More than half of tweets from accounts using the default profile image were no longer available at the end of the tracking period, as were more than a third from accounts with a default bio field. Tweets from these accounts tend to disappear because the entire account has been deleted or made private, as opposed to the individual tweet being deleted.

Posted by unverified accounts.

We also found that removed or deleted tweets tended to come from newer accounts with relatively few followers and modest activityon the site. On average, tweets that were no longer visible on the site were posted by accounts around eight months younger than those whose tweets stayed on the site.

1% of tweets are removed within one hour

3% within a day

10% within a week

15% within a month

Put another way: Half of tweets that are eventually removed from the platform are unavailable within the first six days of being posted. And 90% of these tweets are unavailable within 46 days.

When Online Content Disappears

38% of webpages that existed in 2013 are no longer accessible a decade later BY ATHENA CHAPEKIS , SAMUEL BESTVATER , EMMA REMY AND GONZALO RIVERO

We research words and content for our transcripts. Words that we aren’t sure of, we look up to verify spelling and validity. We got this article from https://www.pewresearch.org/?p=167501. If you’re intrigued, sign up for the Pew Research Newsletter.

Our object is to capture the spoken word, and people make vague references, sometimes to places that no longer exist. Some of the oral histories we transcribe reference events that happened a long time ago—World War II, for example. So we spend a lot of time researching. AI doesn’t verify terms, but we do—we try to verify everything we can.

How they did the study:

How we did this

Pew Research Center conducted the analysis to examine how often online content that once existed becomes inaccessible. One part of the study looks at a representative sample of webpages that existed over the past decade to see how many are still accessible today. For this analysis, we collected a sample of pages from the Common Crawl web repository for each year from 2013 to 2023. We then tried to access those pages to see how many still exist.

A second part of the study looks at the links on existing webpages to see how many of those links are still functional. We did this by collecting a large sample of pages from government websites, news websites and the online encyclopedia Wikipedia.

We identified relevant news domains using data from the audience metrics company comScore and relevant government domains (at multiple levels of government) using data from get.gov, the official administrator for the .gov domain. We collected the news and government pages via Common Crawl and the Wikipedia pages from an archive maintained by the Wikimedia Foundation. For each collection, we identified the links on those pages and followed them to their destination to see what share of those links point to sites that are no longer accessible.

A third part of the study looks at how often individual posts on social media sites are deleted or otherwise removed from public view. We did this by collecting a large sample of public tweets on the social media platform X (then known as Twitter) in real time using the Twitter Streaming API. We then tracked the status of those tweets for a period of three months using the Twitter Search API to monitor how many were still publicly available. Refer to the report methodology for more details.

The internet is an unimaginably vast repository of modern life, with hundreds of billions of indexed webpages. But even as users across the world rely on the web to access books, images, news articles and other resources, this content sometimes disappears from view.

A new Pew Research Center analysis shows just how fleeting online content actually is:

-

A quarter of all webpages that existed at one point between 2013 and 2023 are no longer accessible, as of October 2023. In most cases, this is because an individual page was deleted or removed on an otherwise functional website.

-

For older content, this trend is even starker. Some 38% of webpages that existed in 2013 are not available today, compared with 8% of pages that existed in 2023.

This “digital decay” occurs in many different online spaces. We examined the links that appear on government and news websites, as well as in the “References” section of Wikipedia pages as of spring 2023. This analysis found that:

-

23% of news webpages contain at least one broken link, as do 21% of webpages from government sites. News sites with a high level of site traffic and those with less are about equally likely to contain broken links. Local-level government webpages (those belonging to city governments) are especially likely to have broken links.

-

54% of Wikipedia pages contain at least one link in their “References” section that points to a page that no longer exists.

To see how digital decay plays out on social media, we also collected a real-time sample of tweets during spring 2023 on the social media platform X (then known as Twitter) and followed them for three months. We found that:

-

Nearly one-in-five tweets are no longer publicly visible on the site just months after being posted. In 60% of these cases, the account that originally posted the tweet was made private, suspended or deleted entirely. In the other 40%, the account holder deleted the individual tweet, but the account itself still existed.

-

Certain types of tweets tend to go away more often than others. More than 40% of tweets written in Turkish or Arabic are no longer visible on the site within three months of being posted. And tweets from accounts with the default profile settings are especially likely to disappear from public view.

How this report defines inaccessible links and webpages

There are many ways of defining whether something on the internet that used to exist is now inaccessible to people trying to reach it today. For instance, “inaccessible” could mean that:

-

The page no longer exists on its host server, or the host server itself no longer exists. Someone visiting this type of page would typically receive a variation on the “404 Not Found” server error instead of the content they were looking for.

-

The page address exists but its content has been changed – sometimes dramatically – from what it was originally.

-

The page exists but certain users – such as those with blindness or other visual impairments – might find it difficult or impossible to read.

For this report, we focused on the first of these: pages that no longer exist. The other definitions of accessibility are beyond the scope of this research.

Our approach is a straightforward way of measuring whether something online is accessible or not. But even so, there is some ambiguity.

First, there are dozens of status codes indicating a problem that a user might encounter when they try to access a page. Not all of them definitively indicate whether the page is permanently defunct or just temporarily unavailable. Second, for security reasons, many sites actively try to prevent the sort of automated data collection that we used to test our full list of links.

For these reasons, we used the most conservative estimate possible for deciding whether a site was actually accessible or not. We counted pages as inaccessible only if they returned one of nine error codes that definitively indicate that the page and/or its host server no longer exist or have become nonfunctional – regardless of how they are being accessed, and by whom. The full list of error codes that we included in our definition are in the methodology.

Here are some of the findings from our analysis of digital decay in various online spaces.

Webpages from the last decade

To conduct this part of our analysis, we collected a random sample of just under 1 million webpages from the archives of Common Crawl, an internet archive service that periodically collects snapshots of the internet as it exists at different points in time. We sampled pages collected by Common Crawl each year from 2013 through 2023 (approximately 90,000 pages per year) and checked to see if those pages still exist today.

We found that 25% of all the pages we collected from 2013 through 2023 were no longer accessible as of October 2023. This figure is the sum of two different types of broken pages: 16% of pages are individually inaccessible but come from an otherwise functional root-level domain; the other 9% are inaccessible because their entire root domain is no longer functional.

Not surprisingly, the older snapshots in our collection had the largest share of inaccessible links. Of the pages collected from the 2013 snapshot, 38% were no longer accessible in 2023. But even for pages collected in the 2021 snapshot, about one-in-five were no longer accessible just two years later.

Links on government websites

We sampled around 500,000 pages from government websites using the Common Crawl March/April 2023 snapshot of the internet, including a mix of different levels of government (federal, state, local and others). We found every link on each page and followed a random selection of those links to their destination to see if the pages they refer to still exist.

-

The vast majority go to secure HTTP pages (and have a URL starting with “https://”).

-

6% go to a static file, like a PDF document.

-

16% now redirect to a different URL than the one they originally pointed to.

When we followed these links, we found that 6% point to pages that are no longer accessible. Similar shares of internal and external links are no longer functional.

Links on news websites

For this analysis, we sampled 500,000 pages from 2,063 websites classified as “News/Information” by the audience metrics firm comScore. The pages were collected from the Common Crawl March/April 2023 snapshot of the internet.

Reference links on Wikipedia

For this analysis, we collected a random sample of 50,000 English-language Wikipedia pages and examined the links in their “References” section. The vast majority of these pages (82%) contain at least one reference link – that is, one that directs the reader to a webpage other than Wikipedia itself.

Posts on Twitter

For this analysis, we collected nearly 5 million tweets posted from March 8 to April 27, 2023, on the social media platform X, which at the time was known as Twitter. We did this using Twitter’s Streaming API, collecting 3,000 public tweets every 30 minutes in real time. This provided us with a representative sample of all tweets posted on the platform during that period. We monitored those tweets until June 15, 2023, and checked each day to see if they were still available on the site or not.

Which tweets tend to disappear?

Tweets were especially likely to be deleted or removed over the course of our collection period if they were:

-

Written in certain languages. Nearly half of all the Turkish-language tweets we collected – and a slightly smaller share of those written in Arabic – were no longer available at the end of the tracking period.

-

Posted by accounts using the site’s default profile settings. More than half of tweets from accounts using the default profile image were no longer available at the end of the tracking period, as were more than a third from accounts with a default bio field. Tweets from these accounts tend to disappear because the entire account has been deleted or made private, as opposed to the individual tweet being deleted.

-

Posted by unverified accounts.

We also found that removed or deleted tweets tended to come from newer accounts with relatively few followers and modest activityon the site. On average, tweets that were no longer visible on the site were posted by accounts around eight months younger than those whose tweets stayed on the site.

-

1% of tweets are removed within one hour

-

3% within a day

-

10% within a week

-

15% within a month

Put another way: Half of tweets that are eventually removed from the platform are unavailable within the first six days of being posted. And 90% of these tweets are unavailable within 46 days.

How the Gaza humanitarian aid pier traces its origins to discarded cigar boxes before World War II

Originally published in The Conversation.

Palestinians in Gaza have begun receiving humanitarian aid delivered through a newly completed floating pier off the coast of the besieged territory. Built by the U.S. military and operated in coordination with the United Nations, aid groups and other nations’ militaries, the pier can trace its origins back to a mid-20th century U.S. Navy officer who collected discarded cigar boxes to experiment with a new idea.

Among the artifacts of the military collections of the National Museum of American History, I happened upon these humble cigar boxes and the remarkable story they contain.

In 1939, John Noble Laycock, then a commander in the Navy’s Civil Engineer Corps, was assigned, as the war plans officer for the Navy’s Bureau of Yards and Docks in Washington, D.C., to help prepare for a potential war in the Pacific.

Laycock had to figure out how to construct naval bases on undeveloped islands. The top priority would be what the military called “naval lighterage,” the process of getting cargo and supplies from ships to a shoreline where there were no ports or even piers to dock at.

Text with us for something interesting every day

That’s exactly the problem the relief effort faced in Gaza – and one that military forces and humanitarian groups have faced countless times in the past century.

In the office files of his predecessors, Laycock found plans developed in the 1930s to use small pontoons – essentially floating boxes – that could be easily transported and quickly assembled by hand into larger barges or floating platforms. But Laycock saw problems with the plans’ design and method of connecting the pontoons to each other. And he had an idea.

In my research into his work, I found that around July 1940, Laycock began visiting every concessionaire in the Navy’s headquarters building, which was then located along the National Mall, asking them to save empty cigar boxes for him. Laycock and a helper lined up the boxes and spaced them evenly. Then they linked them together using wooden strips from children’s kites, which they fastened to the corners of the boxes with small nuts and screws.

The simple model demonstrated that it was possible to connect individual, uniformly sized, small pontoon boxes into a much longer, and much stronger, floating beam. Multiple beams could be combined into the base for a platform of any needed size. A big enough platform could support cargo, military trucks and armored vehicles weighing up to 55 tons.

From cigar boxes to steel pontoons

In August 1940, during his family vacation, Laycock figured out how exactly to connect the individual pontoons, which were made of steel and not wood or cardboard like his cigar-box model. He designed steel fasteners – scaled-up nuts and bolts nicknamed “jewelry” that could be inserted and tightened by hand – that could handle the stress of the movement of the ocean beneath a floating platform.

Through trial and error, and applying various military requirements such as the width of the steel plates, weight of the empty pontoon, depth needed to float and load-bearing capacity, Laycock designed a basic pontoon 5 feet high by 7 feet long by 5 feet wide. He also designed a curved section to serve as the bow of a pontoon-based transport vessel. By 1941, testing had proved the design and the system were ready for mass production.

Floating causeways of steel

The pontoon technology first went to war in the South Pacific in February 1942 with the Naval Construction Force, nicknamed the Seabees, who took it to Bora Bora in the Society Islands. The Seabees were pleased with how it worked and helped contribute to the system’s nickname – Laycock’s “magic box.”

The universal nature of the pontoons permitted construction of an array of floating structures, including dredges, barges, floating cranes, workshops, storehouses and gas stations, tug boats, pile drivers and dry docks. These pontoon structures could be found from Guadalcanal to the Marianas, the Aleutians and the Philippines.

The planning for the invasion of Sicily in July 1943 found another use for Laycock’s pontoon system. In late 1942, Royal Navy Capt. Thomas A. Hussey recognized that the Sicilian beaches had gentle slopes. During an invasion, landing craft, especially those designed for tanks, could be expected to run aground several hundred feet from dry land, in water 6 feet deep. Even waterproofed vehicles would be swamped and could sink.

Aware of Laycock’s pontoons, Hussey inquired whether the units could form a floating road, called a causeway, to bridge the gap between ship and shore. Laycock designed a method to build narrow causeways two pontoons wide and 30 pontoons long – roughly 175 feet. Setting them side by side would form a 325-foot floating causeway. They could even be towed or carried by landing craft and deployed upon arrival in shallow water.

Tested successfully in mid-March 1943, the causeways proved a success at Sicily. In 23 days of round-the-clock shifts, the Seabees unloaded over 10,000 vehicles, including trucks, jeeps, half-tracks and towed artillery, on the causeways. Senior American and British leaders said the landings could not have succeeded so rapidly were it not for the pontoon causeways.

Pontoon highways at Normandy

Much like Sicily, the Normandy coast of France also featured beaches with gentle, flat slopes. Floating pontoon causeways were key to the June 6, 1944, D-Day landings for U.S., British and Canadian forces. Engineers would anchor one end of the causeway on the shore and extend the structure out into the ocean far enough that whether it was low or high tide, cargo-carrying vessels could dock without running aground.

Along the sides, every few hundred feet along the causeway, additional pontoons were attached to form piers, so multiple vessels could dock at the same time, regardless of tidal conditions. They could unload directly onto dry pontoons just as they would at any regular pier or dock.

This system allowed a massive, around-the-clock flow of tanks, trucks, artillery, supplies and personnel to support the fighting as the Allied forces moved inland through Normandy over the coming months.

Uses in war and for humanitarian aid

Over the decades, this concept, with technological advancements in construction and fasteners, evolved into pontoon systems used in the Korean and Vietnam wars. Those have since been improved as well and have helped provide humanitarian aid such as in Haiti after a massive earthquake in 2010.

The pier at Gaza involves both parts of the pontoon system – Laycock’s original floating platform as a cargo transfer site 3 miles offshore, and the British-suggested floating causeway and pier system allowing truck deliveries to get to dry land. All from a humble concept model of cigar boxes.Author

Curator of Military History, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

Disclosure statement

Frank A. Blazich Jr. does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Partners

Smithsonian Institution provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

How the Gaza humanitarian aid pier traces its origins to discarded cigar boxes before World War II

Originally published in The Conversation.

Palestinians in Gaza have begun receiving humanitarian aid delivered through a newly completed floating pier off the coast of the besieged territory. Built by the U.S. military and operated in coordination with the United Nations, aid groups and other nations’ militaries, the pier can trace its origins back to a mid-20th century U.S. Navy officer who collected discarded cigar boxes to experiment with a new idea.

Among the artifacts of the military collections of the National Museum of American History, I happened upon these humble cigar boxes and the remarkable story they contain.

In 1939, John Noble Laycock, then a commander in the Navy’s Civil Engineer Corps, was assigned, as the war plans officer for the Navy’s Bureau of Yards and Docks in Washington, D.C., to help prepare for a potential war in the Pacific.

Laycock had to figure out how to construct naval bases on undeveloped islands. The top priority would be what the military called “naval lighterage,” the process of getting cargo and supplies from ships to a shoreline where there were no ports or even piers to dock at.

Text with us for something interesting every day

That’s exactly the problem the relief effort faced in Gaza – and one that military forces and humanitarian groups have faced countless times in the past century.

In the office files of his predecessors, Laycock found plans developed in the 1930s to use small pontoons – essentially floating boxes – that could be easily transported and quickly assembled by hand into larger barges or floating platforms. But Laycock saw problems with the plans’ design and method of connecting the pontoons to each other. And he had an idea.

In my research into his work, I found that around July 1940, Laycock began visiting every concessionaire in the Navy’s headquarters building, which was then located along the National Mall, asking them to save empty cigar boxes for him. Laycock and a helper lined up the boxes and spaced them evenly. Then they linked them together using wooden strips from children’s kites, which they fastened to the corners of the boxes with small nuts and screws.

The simple model demonstrated that it was possible to connect individual, uniformly sized, small pontoon boxes into a much longer, and much stronger, floating beam. Multiple beams could be combined into the base for a platform of any needed size. A big enough platform could support cargo, military trucks and armored vehicles weighing up to 55 tons.

From cigar boxes to steel pontoons

In August 1940, during his family vacation, Laycock figured out how exactly to connect the individual pontoons, which were made of steel and not wood or cardboard like his cigar-box model. He designed steel fasteners – scaled-up nuts and bolts nicknamed “jewelry” that could be inserted and tightened by hand – that could handle the stress of the movement of the ocean beneath a floating platform.

Through trial and error, and applying various military requirements such as the width of the steel plates, weight of the empty pontoon, depth needed to float and load-bearing capacity, Laycock designed a basic pontoon 5 feet high by 7 feet long by 5 feet wide. He also designed a curved section to serve as the bow of a pontoon-based transport vessel. By 1941, testing had proved the design and the system were ready for mass production.

Floating causeways of steel

The pontoon technology first went to war in the South Pacific in February 1942 with the Naval Construction Force, nicknamed the Seabees, who took it to Bora Bora in the Society Islands. The Seabees were pleased with how it worked and helped contribute to the system’s nickname – Laycock’s “magic box.”

The universal nature of the pontoons permitted construction of an array of floating structures, including dredges, barges, floating cranes, workshops, storehouses and gas stations, tug boats, pile drivers and dry docks. These pontoon structures could be found from Guadalcanal to the Marianas, the Aleutians and the Philippines.

The planning for the invasion of Sicily in July 1943 found another use for Laycock’s pontoon system. In late 1942, Royal Navy Capt. Thomas A. Hussey recognized that the Sicilian beaches had gentle slopes. During an invasion, landing craft, especially those designed for tanks, could be expected to run aground several hundred feet from dry land, in water 6 feet deep. Even waterproofed vehicles would be swamped and could sink.

Aware of Laycock’s pontoons, Hussey inquired whether the units could form a floating road, called a causeway, to bridge the gap between ship and shore. Laycock designed a method to build narrow causeways two pontoons wide and 30 pontoons long – roughly 175 feet. Setting them side by side would form a 325-foot floating causeway. They could even be towed or carried by landing craft and deployed upon arrival in shallow water.

Tested successfully in mid-March 1943, the causeways proved a success at Sicily. In 23 days of round-the-clock shifts, the Seabees unloaded over 10,000 vehicles, including trucks, jeeps, half-tracks and towed artillery, on the causeways. Senior American and British leaders said the landings could not have succeeded so rapidly were it not for the pontoon causeways.

Pontoon highways at Normandy

Much like Sicily, the Normandy coast of France also featured beaches with gentle, flat slopes. Floating pontoon causeways were key to the June 6, 1944, D-Day landings for U.S., British and Canadian forces. Engineers would anchor one end of the causeway on the shore and extend the structure out into the ocean far enough that whether it was low or high tide, cargo-carrying vessels could dock without running aground.

Along the sides, every few hundred feet along the causeway, additional pontoons were attached to form piers, so multiple vessels could dock at the same time, regardless of tidal conditions. They could unload directly onto dry pontoons just as they would at any regular pier or dock.

This system allowed a massive, around-the-clock flow of tanks, trucks, artillery, supplies and personnel to support the fighting as the Allied forces moved inland through Normandy over the coming months.

Uses in war and for humanitarian aid

Over the decades, this concept, with technological advancements in construction and fasteners, evolved into pontoon systems used in the Korean and Vietnam wars. Those have since been improved as well and have helped provide humanitarian aid such as in Haiti after a massive earthquake in 2010.

The pier at Gaza involves both parts of the pontoon system – Laycock’s original floating platform as a cargo transfer site 3 miles offshore, and the British-suggested floating causeway and pier system allowing truck deliveries to get to dry land. All from a humble concept model of cigar boxes.Author

Curator of Military History, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

Disclosure statement

Frank A. Blazich Jr. does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Partners

Smithsonian Institution provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.