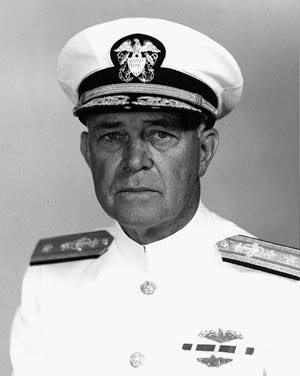

It is commonly said that war is one of the biggest driving forces for technological advancement. This article tells the story of Charles ‘Swede’ Momsen, an innovator and advocate of the U.S. Navy’s submarine fleet who was inspired by his own experience in submarines to create the first primitive underwater rebreather.

In July 1943, the American submarine USS Tinosa was on patrol in Japanese waters when she came across an unescorted oil tanker. It was big at 20,000 tons. There were only a few that size in the Japanese fleet, and her sinking would be a huge blow to the enemy. The Tinosa maneuvered for position at right angles to the lumbering tanker and fired four torpedoes. At least two of them struck their target but none exploded.

Alarmed, the tanker raised speed and fled. The Tinosa fired again from an angle behind. This time two torpedoes hit their target and exploded, leaving the tanker dead in the water. The Tinosa moved in for the kill. At 900 yards the skipper of the Tinosa fired eight more fish at the sitting duck. All failed to explode.

It was the last straw. Since the beginning of the war, submarine skippers had complained that the Navy’s new Mark 6 torpedoes failed to explode on target. Thousands of tons of Japanese shipping had escaped unharmed due to the faulty workings of the Mark 6. Yet, the Division of Naval Ordnance claimed that there was nothing wrong with the torpedoes. They claimed that the failure must be attributable to the crews of the submarines.

The Navy’s Torpedo Problem

When the Tinosa returned to Pearl Harbor, her skipper complained bitterly to the commander of submarines Pacific, Vice Admiral Charles Lockwood. Yet, when the Tinosa’s last torpedo was examined, no defect could be found. Lockwood had a big problem. He had frustrated and angry submariners on the one hand and an intransigent Ordnance Department in Washington on the other. He turned to his friend, Captain Charles “Swede” Momsen, for advice. Momsen was the commander of a submarine squadron but, more importantly, he was a hands-on problem solver who knew how to get things done.

Unwilling to wait for the ponderous Navy bureaucracy in Washington to solve the problem, Momsen suggested that a target range be set up on the nearby island of Kahoolawe. The island has sheer cliffs rising from shallow water. Momsen suggested that torpedoes be fired at the cliffs and any duds be examined.

The first fish ran true and exploded against the cliffs, but the second was a dud and sank to the bottom 50 feet down. Momsen jumped into the water with his snorkel gear, located the torpedo, and supervised the recovery of the live warhead. The torpedo was gingerly lifted onto the deck of the service ship Widgeon and examined. Even with 685 pounds of explosives in the warhead, Momsen did not hesitate to take the exploder apart. He found that the firing pin had not struck the primer cap hard enough to cause an explosion.

The workshops at Pearl Harbor modified the firing pins, and submariners found new lethality in their long, lonely vigils at sea. The Ordnance Department sheepishly admitted to the defect.

Momsen received the Legion of Merit for his successful efforts at discovering and fixing the torpedo problem that had plagued the submarine fleet for a year and a half. It was not the first or the last time that Swede Momsen would save the day.

Requesting Transfer to a “Pigboat”

Born in New York and raised in Minnesota, Momsen was appointed to Annapolis from his hometown of St. Paul. He was commissioned in 1919. After spending two years on the battleship Oklahoma, he requested a transfer to submarines. His commanding officer advised against it. Despite the path of destruction made by German U-boats in the Great War, the Navy was still the realm of the battleships and their advocates. “Pigboat” was the derisive name given to the submarine. Their officers and crews inhabited the lower rungs of the social ladder.

In the 1920s, submarines were cramped and uncomfortable. Duty aboard was primitive with no showers, no toilets, and no refrigeration. Meat spoiled rapidly. Fruit and vegetables lasted little longer. If a submarine should sink, her whole crew could be lost.

In 1925, that is just what happened. In September of that year, the S-51 was inadvertently rammed and sunk by a passing ocean liner. Momsen, in command of her sister ship, the S-1, was the first on the scene of the disaster and the first to find the sunken sub. There was nothing he could do to help the men trapped below, many of whom were his friends. Still living when their sub reached the bottom, the men slowly died when their air ran out.

Innovation Against Naval Bureaucracy

A diving bell rests on the deck of the USS Falcon as the effort to raise the USS Squalus gets underway.

The feeling of helplessness at the loss sparked an idea. He began to think about how such a tragedy could be averted. He came up with the idea of a diving bell that could be guided down to the deck of a sunken sub. If flat plates could be welded as rings around the fore and aft hatches of all submarines in advance, the descending bell, or rescue chamber, could form a seal with the plate, the hatch could be opened, and survivors brought safely to the surface.

When he had fleshed out his ideas, he presented them to his base commander, Captain Ernest J. King, who later served as chief of naval operations during World War II. King endorsed the idea and sent it on to the Navy Bureau of Construction and Repair for evaluation. It was Momsen’s first experience with a hidebound naval bureaucracy. He heard nothing for a year. He thought his idea had been rejected out of hand as unworkable.

Toward the end of 1926, Momsen was due for a transfer to shore duty. To his surprise he was assigned to the Bureau of Construction and Repair to the very desk where he had sent his rescue chamber idea. On his first day of duty he rummaged through the “in” basket on his desk. There at the bottom, untouched from the day it had been received a year earlier, was his submission. He was furious.

His rage gave way to renewed determination. He began to push for the evaluation of his idea and was met with disdain and derision. It was impudent of him to be so pushy about an idea, his own idea at that. His design was summarily rejected.

The Momsen Lung

Then fate intervened. Shortly after his proposal was turned down, another submarine was inadvertently sunk. The S-4 lay on the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean near Cape Cod, 110 feet down. Her crew was still alive as their ship lay there. They were able to tap out messages to the surface as they slowly consumed all of the breathable air and one by one died in their watery tomb.

There was outrage from Congress and the public alike. Something had to be done to save the crews of submarines. In the meantime, Momsen had another idea, which he would pursue without going through official channels. He wanted to avoid bureaucratic interference. It was a simple idea that did not require official evaluation or approval for construction of a prototype.

Seaman A.L. Rosenkotter aboard the submarine V-5, later named USS Narwhal, demonstrates the use of the Momsen Lung and the after escape hatch aboard the sub in July 1930.

With a group of volunteers, he began work on a personal breathing bag that a man could strap to his chest and use to ascend from a sunken sub. The device would contain breathable air that on the surface could be used as a flotation device. The inflatable bladder soon earned the nickname, the Momsen Lung.

Enlisting a civilian engineer, Momsen began work on a prototype. The finished product, made of discarded inner tube, looked for all the world like a hot water bottle. Tests were begun in diving tanks with volunteer divers. Momsen always dove first at each new depth. By late 1928, he decided to demonstrate his lung. He chose a spot in Chesapeake Bay that was 110 feet deep, the same depth that the S-4 had sunk, and was lowered to the bottom in a modified bell. He rose to the surface by breathing the air in his Momsen Lung and proved the validity of his design.

All of this work had been done on a shoestring and outside of official Navy channels. The brass learned of Momsen’s success the same way that the rest of the world did, in the newspapers. Embarrassed by his success and yet anxious for it as well, the admirals now gave their blessing to his research on the lung and the rescue chamber.

Momsen next demonstrated that he could ascend from 200 feet down using the lung. The Momsen Lungs became standard equipment on submarines, and all personnel had to be qualified in their use before becoming submariners.

The Rescue Bell Sees Action

Momsen then turned his attention to the rescue bell. Five feet wide and seven feet tall, the bell was designed to winch its way down to a stricken sub along a line that a deep sea diver had attached to the hatch of the sub. The chamber formed a watertight seal against the flat plates that were welded around the hatches of all new and existing submarines.

Momsen was continually testing and improving the design of his inventions with a small crew of dedicated deep-sea divers. While in the midst of testing, with a diver in the tank on May 23, 1939, he got a phone call. The newest submarine in the fleet, the USS Squalus, was missing and presumed lost at sea. The Navy turned to Swede Momsen as the only man capable of rescuing survivors at the bottom of the ocean.

Following the tragic loss of the submarine USS Squalus, U.S. Navy deep sea divers don suits during rescue and salvage operations.

The Squalus had been in the midst of a shakedown cruise when her captain ordered a dive. When a ventilation valve failed to close, the Squalus rapidly filled with water and sank to a depth of 240 feet off Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Thirty-three members of her crew of 59 were able to close themselves into the control room and forward torpedo room but could not raise their ship. The captain considered it too great a risk to allow his wet and shivering crew to use the Momsen Lung in the frigid waters.

Momsen and his deep-sea diving team were rushed to the scene. A buoy from the stricken sub bobbed on the surface marking its location, but an accident snapped the cable. Communication with the sub was lost. Worse, so was its location. One of Momsen’s divers located the sub on the bottom and attached a cable to the forward hatch. The rescue chamber slowly winched down with two of his crewmen to effect the rescue.

Meanwhile, aboard the Squalus the surviving crewmen shivered against the wet and cold of their undersea prison. They had been down for over 24 hours by the time the bell came to rest on the forward hatch. The rescue chamber’s crew brought sandwiches, coffee, and blankets for the crew who would not be able to make the first ascent. The most exhausted and weakest men went first. When they reached the surface they were taken aboard Momsen’s rescue ship, the Falcon. The chamber descended again to fetch more crew members. The captain of the Squalus was the last to leave.

Resuscitating the Squalus

The rescue of the crew of the Squalus was a worldwide public relations windfall for the Navy, and Momsen was a hero. His success was punctuated by the fact that other nations were losing submarines around the same time and had no way to rescue their crews. For “the Swede” there was no time to celebrate. The next task for his intrepid crew of deep-sea divers was to raise the Squalus from its watery grave.

It was the deepest salvage job ever attempted at that time, and it too was successful. The Squalus was brought back to port, refurbished, and recommissioned as the USS Sailfish. She would fight and survive the upcoming war with 12 missions to her credit.

The USS Falcon and the submarine USS Sculpin take up position during the effort to raise the sunken Squalus from the ocean floor.

Swede Momsen continued his work on deep-sea diving and rescue techniques. He experimented with a breathable mixture of oxygen and helium to give divers a longer effective work time in the deep while continuing to perfect the rescue chamber and the lung.

He was stationed at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, as an operations officer when he had an early morning call. A destroyer, the USS Ward, reported sinking an unidentified submarine. Without consulting his superiors as protocol demanded, Momsen dispatched another destroyer, the Monahan, to investigate. The Monahan reported excitedly that she had rammed another unidentified submarine. But by that time all hell had broken loose as Japanese planes launched their dastardly attack. The Monahan was the only American warship ordered into action before the air raid began. From his office, Momsen watched helplessly as the battleship USS Arizona blew up.

Revolutionizing the Silent Service

Crewmen aboard the stricken submarine USS Tang put on Momsen Lungs as they attempt to reach the surface, 180 feet above, in October 1944. Only eight members of the Tang’s crew survived.

As the war progressed, Momsen was given command of a submarine squadron based in Hawaii. It was in this assignment that he risked his life while swimming over the live torpedo.

Following a stint at a desk job in Washington, D.C., Momsen returned to Hawaii and his beloved submarines. The Germans had successfully used wolfpack tactics in the Atlantic, but American submarines acted alone. As more subs came down the ways, it was feasible to start thinking about using them to hunt together.

Momsen gave himself the assignment of developing tactics unique to the Pacific War. In the Atlantic, the Allies were able to put together large convoys from a growing number of new ships. The Japanese suffered from a dwindling amount of shipping. Their convoys rarely amounted to more than a dozen or so freighters and tankers.

Momsen reasoned that for such a small target only three submarines would be necessary. Two would attack on either flank of a convoy, and one would trail behind, finishing off damaged ships. In October 1944, he got to put his theory to the test when he led the first American wolfpack against Japanese shipping. The three submarines under his command sank five ships and damaged eight others on their first patrol. The new strategy became commonplace for the rest of the war. This time Momsen was awarded the Navy Cross. With reliable torpedoes and improved tactics, the Silent Service soon swept Japanese shipping from the sea.

Silk Bags: The Static Danger

As a reward, Swede Momsen was given a plum assignment, command of his own battleship, the USS South Dakota. Under his command the mighty battleship supported operations on Iwo Jima and Okinawa. One day while the ship was taking on ammunition there was a series of explosions in the forward turrets as the forward magazines ignited, killing several sailors and threatening to destroy the ship. Timely flooding of the remaining magazines prevented the South Dakota from blowing up.

At the time, powder was stored in silk bags and housed in steel drums. Momsen concluded that friction between the steel casing and the silk bags caused a spark of static electricity, which ignited the disaster. His old nemesis, the Bureau of Ordnance, refused to believe it. He had burned them over the torpedo warhead incident, and he was not their favorite officer. But Momsen had enough clout to conduct his own tests on the matter. When simulated handling of powder proved that the rubbing of silk against steel could cause a spark, the Navy ceased using silk for the storage of powder.

Momsen After the War: Returning to his Submarines

After the war, Momsen was reassigned to his first love, submarines. He wanted to come up with a design for a submarine that would optimize speed. Yet he knew that if he went through official channels to design such a boat he would be constantly scrutinized, second guessed, and discouraged. So, he proposed to head a design team that would develop a submarine target, something for surface ships to shoot at. The ploy worked, and the Navy left him alone.

Meanwhile, he instructed his designers to sacrifice every consideration for the sake of underwater speed. “When in doubt, think speed,” he told them. The result of his clandestine project was the bullet-shaped hull of his prototype, the USS Albacore, in 1953. She could reach underwater speeds of 30 knots in short bursts and turn on a dime. The hunter-killer surface ships that went after her were helpless against her speed and maneuverability. When Swede Momsen’s design was married to nuclear power, the submarine achieved an exalted place in the Navy’s offensive capability.

When Vice Admiral Momsen retired from the Navy, he was considered by many, not including those whose toes he had stepped on, to be the nation’s foremost submariner. He died of cancer in 1967 at the age of 70, and an Arleigh Burke-class guided missile destroyer, USS Momsen, is named in his honor.